Here’s an interesting question: why does your pastor have authority over you?

This question can sometimes go unasked or unanswered, but when it is, the actual answers provided leave something to be desired.

Before I converted to Catholicism, as a Protestant, I intuitively accepted the authority of pastors over me if I considered them “anointed”, wise, or if they’d founded or inherited the leadership of the church I attended.

It took me years to realise these weren’t good answers. It also took me a while to realise that asking these questions wasn’t a sign of rebelliousness or arrogance.

So I invite you to question with me…who or what gave your pastor authority?

In this post, I’ll be sharing the possible answers some people give to this fundamental question, why they don’t line up, and then finally what I feel is the only legitimate answer.

Table of Contents

- Answer #1: Character & Skillset

- Answer #2: Anointing & Call

- Answer #3: Theological Credentials

- Answer #4: Church Founder

- Answer #5: Inheritance

- Problems to Each Answer Explained

- The Best Answer: Apostolic Succession

- Why Apostolic Succession Is Right

Possible Answer #1

Character & Skillset

Summary:

Having a tested, proven and consistently good character and strong skillset to effectively lead is the reason why my pastor has authority over me.

Problems:

✘ People without authority are assigning the authority

✘ No objective standard to agree on

✘ Sheep shouldn’t choose their shepherds

✘ Lack of biblical support

✘ Lack of patristic support

Possible Answer #2

Anointing & Call

Summary:

Having an anointing and a special call from the Lord to shepherd and lead is the reason why my pastor has authority over me.

Problems:

✘ People can’t agree on what “anointing” means or looks like

✘ No clear way of knowing whether it’s a genuine call from God

✘ Unstable authority

✘ Lack of biblical support

✘ Lack of patristic support

Possible Answer #3

Theological Credentials

Summary:

Having competent theological knowledge and credentials due to obtaining a Theology degree or undergoing seminary training or some kind of dedicated study is the reason why my pastor has authority over me.

Problems:

✘ Lay people in congregations can have theological credentials

✘ It assumes that any institution can assign legitimate authority

✘ Lack of biblical support

✘ Lack of patristic support

Possible Answer #4

Church Founder

Summary:

My pastor planted or founded my church, therefore this is the reason why my pastor has authority over me.

Problems:

✘ Where did they get the authority to plant or find a new church?

✘ Treats church like a business and pastors as business owners

✘ Lack of biblical support

✘ Lack of patristic support

Possible Answer #5

Inheritance

Summary:

Being the child or successor of the pastor and inheriting their authority is the reason why my pastor has authority over me.

Problems:

✘ Why presume the original pastor had legitimate authority to pass on?

✘ Treats church like a business and pastors as business owners

✘ Lack of biblical support

✘ Lack of patristic support

To skip down to what I feel is the best answer to this question, click here.

Alternatively, you can understand more each of the problems I’ve listed above by carrying on reading down below.

Problems to Each Answer Explained

Answer #1’s Problems:

✘ People without authority are assigning the authority

Type of fallacy: Logical

This answer is logically flawed because the people assigning the pastor authority have no authority in of themselves to assign that authority in the first place.

If it’s presumed they have the authority to assign authority, the question is pushed back a stage and begs the question who gave them authority.

Furthermore, whatever “authority” their leader would gain would exist only in the minds of those same people who selected and continue to vouch for their leader.

Problematically, those who rescind their approval of their leader or who never granted it in the first place would find no real reason to view their pastor as having authority.

And how could Christ’s Church function like this without breaking down into division?

Moreover, if one would try to circumvent this argument by pointing out a leadership committee chose their pastor, then likewise from whom or what did the leadership committee obtain authority?

Additionally, if one would semantically object to the idea that people are the ones “assigning” the authority and would assert instead that the authority comes directly from God, then this is a larger and altogether different problem that is dealt with below.

✘ No objective standard to agree on

Type of fallacy: Practical

Assessments of intangible qualities such as skillsets, character, anointing or orthodoxy are inherently subjective and people will inevitably disagree with one another.

Therefore if a pastor gains authority due to these qualities, there will be those who will not recognise their authority because they do not recognise the reality, authenticity or value of these qualities.

This, at worst, will lead to division and splits in congregations and, at best, disgruntled members of the congregation who do not respect their leader’s authority.

✘ Sheep shouldn’t choose their shepherds

Type of fallacy: Prudential

If the role of a Christian leader or pastor is to help shepherd the body of Christ, why then should sheep choose their own shepherds?

Even if hypothetically sheep had the authority to choose their own shepherds, since when do sheep know what’s best for them?

✘ Lack of biblical support

Type of fallacy: Theological

Biblical data suggests God calls leaders not merely on account of their character or skillset, but in accordance with His specific will for a specific purpose and time.

Isaiah 3 talks about God making “babes” and “boys” rulers as punishment for Judah’s disobedience.

The Levitical priesthood was a position of leadership passed on generationally.

Moreover, mainstream Judaism claims that authority originating from Moses was passed down century-to-century from rabbi to student by ordination. In support of this, Numbers 27:18 sees Moses passing on authority to Joshua in this fashion.

St. Paul, who trained under a later rabbi in this chain (Acts 22:3), dutifully respects the high priest Ananias’ authority even when unfairly treated by him and despite the priest’s inability to comprehend the Gospel. (Acts 23:5)

King David was also compromised morally and wasn’t the strongest of his brothers to face Goliath, but was still chosen by God to a position of authority in 1st Samuel 16.

In 1st Timothy 5:22, St. Paul warns Timothy not to “lay hands on” anyone hastily, showcasing a New Testament parallel to how Moses passed on his authority to Joshua by the laying on of hands in the Old Testament.

And in Titus 1:5, St. Paul directs St. Titus to “ordain presbyters in every town”.

Many more counter-arguments from Scripture could be given to further illustrate how authority was viewed, given and passed on in the Bible.

✘ Lack of patristic support

Type of fallacy: Theological / Historical

Early Christian writing shows that authority was passed on by ordination via the laying on of hands in a manner similar to 1st Timothy 5:22 and Numbers 27:18.

St. Irenaeus of Lyon, a Greek bishop from the 2nd-century, wrote the following in 189AD,

“It’s possible, then, for everyone in every church, who may wish to know the truth, to contemplate the tradition of the Apostles which has been made known to us throughout the whole world. And we’re in a position to enumerate those who were instituted bishops by the Apostles and their successors down to our own times.”

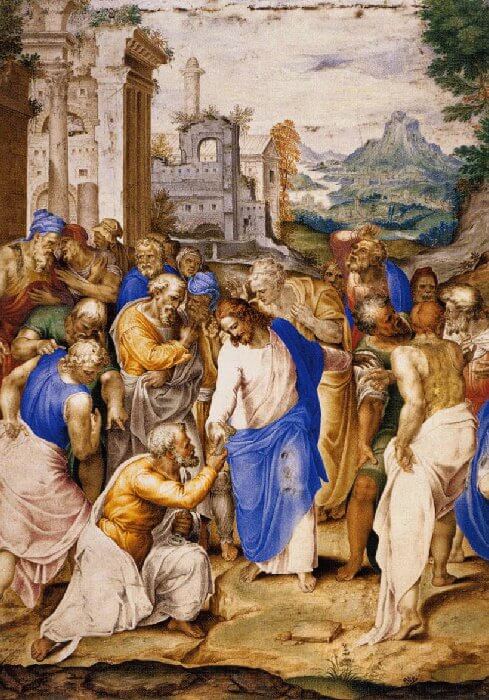

Pope St. Clement of Rome, writing around 96AD in his Epistle to the Corinthians, even spells out Jesus’ motive for choosing Apostolic succession as the vehicle to pass on authority.

“Our apostles also knew, through our Lord Jesus Christ, that there would be strife on account of the office of the episcopate. For this reason, therefore, inasmuch as they had obtained a perfect fore-knowledge of this, they appointed those ministers already mentioned, and afterward gave instructions, that when these should fall asleep, other approved men should succeed them in their ministry.”

These two quotes, along with many other quotes from the Church Fathers, show two qualities:

- Ordination was necessary to obtain authority in the early Church.

- The person doing the ordaining had to be a successor to the Apostles.

Answer #2’s Problems:

✘ People can’t agree on what “anointing” means or looks like

Type of fallacy: Practical

In my years as a Protestant, the word “anointing” had a loose definition.

It was sometimes used to describe someone gifted, e.g. a good singer could be described as “anointed”, meaning they could invoke an emotional response that made one feel close to God.

A Bible teacher could be described as “anointed” if their teaching was dynamic, relevant or hard-hitting.

Or someone taking on a leadership role would be prayed for to receive God’s “anointing” for the role.

In short, each example shows the slippery and diverse meaning “anointing” employed.

It also highlights the subjective nature of describing someone as “anointed”; what one person may call “anointed” wasn’t and is never unanimous.

For example, one worship leader’s voice may be “anointed” for one person, yet not for another.

Therefore, if one person is assigned authority based on their “anointing”, what occurs is that potential leaders are at the mercy of what other’s perceive as anointed, meaning that the congregation ultimately chooses their own leader.

✘ No clear way of knowing whether it’s a genuine call from God

Type of fallacy: Practical

If a leader claims to have received a mandate or call from God to lead, there’s no true way of confirming this.

Even if the leader is sincere in their personal belief, there’s also no way of knowing the validity of their subjective experience that lead them to believe they were called to lead in the first place.

St. Paul’s personal experience of Jesus on the road to Damascus (Acts 9) that ultimately led him to become an apostle, was verified by a pre-existing authority in Galatians 2:9.

If no such verification can come from a pre-existing authority, then one cannot be assigned authority simply due to a subjective experience.

✘ Unstable authority

Type of fallacy: Prudential

If someone is assigned authority based on a subjective perception of their “anointing”, then if that “anointing” is lost, then so is their authority.

This effectively creates a purely performance-based authority which is highly unstable and an ineffective long-term mechanism for shepherding Christ’s flock.

✘ Lack of biblical support

Type of fallacy: Theological

In the Bible, an “anointing” is a ritual act rather than a subjective perception of an individual’s skills.

Biblical anointing, usually the smearing of the head by oil, was supposed to introduce God’s presence into a person’s life for a specific purpose.

The most well-known example being the anointing of Israelite kings to help them rule righteously.

However, even when an “anointing” included a non-physical act, e.g. the anointing of Jesus by the Holy Spirit during his baptism (Isaiah 61:1, Matthew 3:16), it was still a visible event with obvious historical significance.

Therefore, pointing at a particular individual’s skills and personally believing them to be anointed (and therefore “called” by God), isn’t a Biblical model for assigning authority.

✘ Lack of patristic support

Type of fallacy: Theological / Historical

The Church Fathers do not support this model of authority but instead support the ordination of bishops and priests.

Where, under this correct Biblical model, ordination will include anointing as a ritual act rather than a subjective assessment of an individual’s skills.

Answer #3’s Problems:

✘ Lay people in congregations can have theological credentials, as well as atheists

Type of fallacy: Logical

This isn’t a sound answer since members of congregations without any leadership or authority can have excellent theological knowledge and credentials.

Moreover, even atheists who aren’t Christians can hold Theology degrees.

If authority to lead and teach is dependent purely on theological credentials, then another question is when is knowledge enough knowledge and which knowledge in particular is essential?

✘ It assumes that any institution can assign legitimate authority

Type of fallacy: Logical

Just because an institution or seminary awards a degree or certificate, doesn’t de facto translate as having authority in Christ’s Church.

After all, Christ’s Church existed long before institutions like universities and seminaries as we know them today.

While legitimate pre-existing authorities may require prospective candidates to possess theological credentials, it doesn’t seem justified to believe having the credentials alone are enough.

✘ Lack of biblical support

Type of fallacy: Theological

Many Biblical characters chosen by God to lead His people weren’t necessarily the most knowledgable.

While one does find some leaders as having studied extensively beforehand, e.g. the Apostle Paul studying “at the feet of Gamaliel” (Acts 22:3), this doesn’t appear to be a strict criterion.

Many characters preparing for leadership roles via ordination in the priestly, rabbinical, or ministerial capacity were trained in their theological knowledge, but it was training or suitability for the job rather than an automatic guarantee.

✘ Lack of patristic support

Type of fallacy: Theological / Historical

The early Church Fathers were highly knowledgeable in Theology, and some of them had incredible credentials, such as hearing the Apostles themselves preach.

However, their writings show their tendency to support their teachings by appealing to their authoritative link to the Apostles.

Thus their authority didn’t come from their personal understanding or credentials, but from how they were authoritatively linked to the Apostles in passing on the faith pure and undistorted.

It was this direct Apostolic link, passed on via ordination through the laying on of hands that vouched for their teaching authority.

Heretics also understood the significance of this. They would often name their fake gospels written centuries later after the names of Apostles (or at least those linked to the Apostles.)

Answer #4’s Problems:

✘ Where did they get the authority to plant or find a new church?

Type of fallacy: Logical

Planting or finding new churches implies authority to the person doing the planting or finding.

Therefore, if a pastor’s authority stems from them planting or finding the church you attend, the original question and problem remain.

✘ Treats church like a business and pastors as business owners

Type of fallacy: Theological

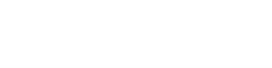

Since Jesus is the founder of His Church (Matthew 16:18) and the fact that the Church is Christ’s body (1 Corinthians 12:27), we should therefore expect it to look and behave differently to other institutions.

People finding and planting their own churches, to which they then become the leader, receiving financial contributions, making business decisions, and trying to grow their specific brand of “church” is too worldly.

This type of activity also breeds a consumeristic attitude among congregations, whereby people move churches and hear teachings that specifically suit and justify their lifestyles.

It also creates more division among Protestant groups whereby people feel they have the liberty to plant their own churches and divide congregations whenever they find it necessary.

✘ Lack of biblical support

Type of fallacy: Theological

In God’s word, we find no instance where a moral individual felt at liberty to start their own church.

However, we do find repeated admonitions not to fall into the sin of schism against God’s leaders. (1 Corinthians 12:25-27)

We also find the following:

- God swallowing up the ground to destroy Korah’s people rebellion against Moses (Numbers 16:1–40)

- St. Paul commanding us to “have nothing more to do” with someone who “stirs up division”. (Titus 3:10-11)

- God giving authority to the Twelve Apostles as leaders of His Church (Matthew 18:18, Matthew 19:28, Matthew 10:1, etc.)

- St. Paul confirming this hierarchy in Ephesians 2:20

- St. Peter rebuking someone offering money to obtain a similar authority (Acts 8:18-20)

Therefore it seems clear that using money to purchase or rent a building and host meetings doesn’t give anyone the legitimate authority to lead in Christ’s Church.

✘ Lack of patristic support

Type of fallacy: Theological / Historical

In the days of the Church Fathers, it was the heretics who presumed they had the authority to plant and find their own church.

In numerous quotes, we see how the Church Fathers found this presumptuous act sinful and scandalous.

Answer #5’s Problems:

✘ Why presume the original pastor had legitimate authority to pass on?

Type of fallacy: Logical

For a successor to obtain legitimate authority, it requires the person passing on the baton to actually have legitimate authority themselves.

A pastor may own a building, possess the respect of their congregation, and even be a competent leader, but unless their authority came licitly then, in Christ’s Church, they actually have no real authority to pass on.

✘ Treats church like a business and pastors as business owners

Type of fallacy: Theological

In God’s word, we find no instance where a moral individual felt at liberty to start their own church and then pass on their authority to a successor.

In the case of biblical succession, such as in Numbers 27:15–23 where Moses passed on his authority to Joshua, the authority is always legitimate and not presumed.

Therefore it seems clear that, while a business owner may presume to have legitimate authority to pass to an heir, this same presumption does not hold up in Christ’s Church.

This issue of pastors acting like business owners was explored more above.

✘ Lack of biblical support

Type of fallacy: Theological

As already alluded to in my answers above, Scripture portrays a different kind of succession than the type portrayed in Protestant congregations passing on authority to successors.

The key difference is that this authority is always legitimate at the source and, if abrogated generationally, is clearly explained.

✘ Lack of patristic support

Type of fallacy: Theological / Historical

The Church Fathers often talk about succession.

The key difference between the succession of one pastor passing on authority to their successor and the Church Father’s type of succession is summed up in one word: Apostolic.

For the Church Fathers, valid succession is inexplicably linked with valid authority.

In their minds, valid Church authority began with Jesus giving it to His Apostles.

The Twelve Apostles then, under the instruction of Jesus, passed it on to successors for the next generation.

It’s in this vein that the Church Fathers are concerned with succession. If a succession couldn’t be linked back to one of the Twelve, then it wouldn’t be considered valid.

So in this way, the Church Fathers would’ve rejected the type of succession one sees in Protestant congregations where a pastor passes on their supposed authority to a successor.

The Best Answer: Apostolic Succession

Having considered the flaws of each alternative answer, I’ve come to the conclusion that there is only one unproblematic answer to this question.

If you’ve read my explanations for each problem above, then you’ve probably already figured it out.

And, before I start talking about this answer, it should be noted that this isn’t a novel or unknown answer.

In fact, the majority of Christians worldwide hold to it too.

This answer, as the title of this post reveals, is Apostolic succession…But what is Apostolic succession?

Apostolic succession is, according to Google, “the uninterrupted transmission of spiritual authority from the Apostles through successive popes and bishops, taught by the Roman Catholic Church but denied by most Protestants.”

(It must be said that Anglicans, Orthodox and Copts also hold to Apostolic succession too.)

In layman’s terms, this belief means that Church authority began with Jesus giving it to His Apostles (Matthew 10:1, 18:18, and 19:28), who then gave it to hand-selected successors, and so on down through the ages.

But why is this mechanism effective? Let’s briefly consider how this answer succeeds where the others failed.

Why Apostolic Succession Is Right

Is Apostolic Succession Logical?

Apostolic succession doesn’t fall for the same logical fallacies as the other proposed answers since the leader passing on their authority possesses a credible reason for their own authority.

This credible reason is their historical link to the Twelve Apostles who, in turn, received their authority from Jesus.

In short, we can conclude that Apostolic succession is logical.

Is Apostolic Succession Practical?

The authority of the leader with Apostolic succession also doesn’t rely on skillsets, character, “anointing” (whatever that means), or an untestable claim to having a special “call” from God.

The authority is objective and clearcut which makes it practical, undeniable and effective.

While skills, character, “anointing” and “call” are of course essentials to the role, this answer doesn’t crumble under the weight of subjective interpretations of these qualities.

We can thus conclude that Apostolic succession is practical.

Is Apostolic Succession Prudent?

Apostolic succession doesn’t entail the congregation choosing their own shepherds.

This is because candidates of Apostolic succession are hand-chosen by pre-existing authority—shepherds who understand first hand the needs of the sheep, their historical role in the Apostolic line, and what the call of God to shepherd in His Church means.

Moreover, the authority of those with Apostolic succession is stable since it cannot be rejected by the sheep.

We can, therefore, surmise that Apostolic succession may be the best mechanism to effectively shepherd Christ’s flock in the long-term, and can thus consider it prudent.

Is Apostolic Succession Biblical?

Unlike the other possible answers on offer, Apostolic succession has a lot going for it in terms of biblical data.

First of all, it’s never contradicted by the Bible but is actually supported implicitly in many places and even explicitly in others.

While some may deem it a “tradition of men” (to use the language of Mark 7:8), this is a weak argument since it’s assuming it’s man-made without any evidence.

And if Apostolic succession is a godly tradition then, according to 1 Corinthians 11:2 and 2 Thessalonians 2:15, it should be “maintained” and “held fast” to.

But is it a godly tradition?

Acts 1:21-26 sees the Apostles immediately switching over Judas’ apostleship to St. Matthias. This shows apostolic authority being passed on after Jesus’ ascension to Heaven.

Moreover, in 1 Timothy 4:14, St. Paul talks about St. Timothy’s “gift” and authority as having come from “the laying on of hands by the presbytery.”

In 2 Timothy 2:2, St. Paul also instructs St. Timothy, “what you have heard from me through many witnesses entrust to faithful people who will be able to teach others as well.”

But in 1 Timothy 5:22, St. Paul also warns St. Timothy not to “ordain anyone hastily” and significantly, the Greek word for “ordain” here literally means “lay hands on”.

These two verses show the concern the apostle Paul had to pass on the Faith to “faithful people” of the next generation and to not ordain leaders hastily.

Biblically, this shows the need for Apostolic succession to pass on the Faith whole and pure.

Furthermore, in the Old Testament, Numbers 27:15–23 and Deuteronomy 34:9 explains Joshua’s authority as having come from when Moses “laid his hands on him and commissioned him”.

Thus there is some significant evidence that authority—both in the Old and New Testament Scriptures—was passed on generationally by the laying on of hands from pre-existing authority.

So there certainly seems to be evidence for Apostolic succession (as well as the need for it) in the Bible.

Is Apostolic Succession Historical?

The question of whether Apostolic succession is biblical or not becomes even clearer when looking at the witness of early Christian history.

In the writings of both the Apostolic and Church Fathers, we see a unanimous defence of Apostolic succession.

This is highly significant because some of these Christian writers knew the Apostles personally. Therefore what they teach can help clarify what the Apostles taught.

Pope St. Clement of Rome, who is traditionally identified as the “Clement” mentioned in Philippians 4:3, wrote the following around 95AD:

“Through countryside and city [the apostles] preached, and they appointed their earliest converts, testing them by the Spirit, to be the bishops and deacons of future believers. Nor was this a novelty, for bishops and deacons had been written about a long time earlier…Our apostles knew through our Lord Jesus Christ that there would be strife for the office of bishop. For this reason, therefore, having received perfect foreknowledge, they appointed those who have already been mentioned and afterwards added the further provision that, if they should die, other approved men should succeed to their ministry.”

St. Hegesippus, who was most likely a Jewish convert and so probably familiar with the rabbinical succession of Judaism, writes in his memoirs around 180AD:

“When I had come to Rome, I [visited] Anicetus, whose deacon was Eleutherus. And after Anicetus [died], Soter succeeded, and after him Eleutherus. In each succession and in each city there is a continuance of that which is proclaimed by the law, the prophets, and the Lord.”

St. Irenaeus, a Greek bishop noted for his role in guiding and expanding Christian communities in what is now the south of France, writes in his sterling work, Against Heresies, in 189AD:

“It is possible, then, for everyone in every church, who may wish to know the truth, to contemplate the tradition of the apostles which has been made known to us throughout the whole world. And we are in a position to enumerate those who were instituted bishops by the apostles and their successors down to our own times, men who neither knew nor taught anything like what these heretics rave about.”

St. Irenaeus also mentions in this work, “It would be too long to enumerate in such a volume as this the successions of all the churches”.

Finally (though I could’ve quoted more) Tertullian, writing around 200AD, mentions how Apostolic succession is a safeguard against false teaching:

“But if there be any [heresies] which are bold enough to plant [their origin] in the midst of the apostolic age, that they may thereby seem to have been handed down by the apostles, because they existed in the time of the apostles, we can say: Let them produce the original records of their churches; let them unfold the roll of their bishops, running down in due succession from the beginning in such a manner that [their first] bishop shall be able to show for his ordainer and predecessor some one of the apostles or of apostolic men—a man, moreover, who continued steadfast with the apostles. For this is the manner in which the apostolic churches transmit their registers: as the church of Smyrna, which records that Polycarp was placed therein by John; as also the church of Rome, which makes Clement to have been ordained in like manner by Peter.”

One Final Proof: Judaism

Alluded to in my quotation of Numbers 27:15–23 and St. Hegesippus is the role Judaism has in proving Apostolic succession to be true.

“By what authority do you do these things?” the Pharisees once asked Jesus.

The Pharisees, history shows, were the descendants and recipients of Moses and his authority.

But in fact, the Bible affirms this too when Jesus, in Matthew 23:2-3, says, “the scribes and the Pharisees sit on Moses’ seat. So practice and observe everything they tell you.”

Hardly any Jew would have respected the Pharisees claim to authority because a few Jews thought they were gifted or “anointed”, or because a committee of Jewish men got together and voted the Pharisees in.

It was because the Pharisees claimed succession all the way back to Moses.

And in fact, according to the Talmud, the scribes and the Pharisees actually could demonstrate that their authority went back to Moses himself.

Here is a Talmudic verse (Pirkei Avot 1:1) that supports the Pharisees’ claim:

“Moses received the Torah from Sinai and transmitted it to Joshua, and Joshua to the Elders, and the Elders to the Prophets, and the Prophets transmitted it to the Men of the Great Assembly.”

The first-century Romano-Jewish historian, Josephus, also writes in his Antiquities of the Jews, Book XIII, Chapter 10:

“What I would now explain is this, that the Pharisees have delivered to the people a great many observances by succession from their fathers, which are not written in the laws of Moses”

The Pharisees, therefore, had the authority to deliver to the people “a great many observances” precisely because of their succession from “their fathers”.

Furthermore, by saying, “which are not written in the laws of Moses”, Josephus here alludes to the Oral Torah, which was the Law of Moses that hadn’t been written down but was passed down orally from generation to generation.

The belief in the Oral Torah exacerbated the need for the authoritative succession of scribes in order to protect these oral teachings.

The Protestant early Christian historian J. N. D. Kelly writes in his book, Early Christian Doctrines, the following:

“Where in practice was the apostolic testimony or tradition to be found? …The most obvious answer was that the apostles had committed it orally to the Church, where it had been handed down from generation to generation. …Unlike the alleged secret tradition of the Gnostics, it was entirely public and open, having been entrusted by the apostles to their successors, and by these in turn to those who followed them, and was visible in the Church for all who cared to look for it.”

And hence we see that, in a sense, Christianity also has its “Oral Torah”; the oral Traditions from Jesus passed down the centuries via Apostolic succession.

This thus makes Apostolic succession all the more necessary and appropriate.

I hope you enjoyed this post exploring the question of leadership in Christ’s Church.

Feel free to comment below with your questions or thoughts. I look forward to hearing from you!